Adiós Ayacucho

(1990)

Narration by Julio Ortega, in Theatrical Version and Direction by Miguel Rubio

Narration by Julio Ortega, in Theatrical Version and Direction by Miguel Rubio

A solo performance by Augusto Casafranca

Production: Socorro Naveda

Technical Coordination: Alejandro Siles

In Goodbye Ayacucho, Alfonso Cánepa, an Ayacucho farmer who was a victim of the violence of the 1980s in Peru, decides to travel from Ayacucho to Lima to ask the President of the Republic for help in recovering the parts of his body that, he believes, were taken to the capital by his assailants.

NOTES ON THE CREATION

When we came across Goodbye Ayacucho by Julio Ortega, we felt that our project would not be complete without a reference to this other migration — the continuous, almost futile, pilgrimage of the families of disappeared peasants who came to Lima to ask for justice. Ortega’s story moved us deeply, as it encapsulated a moment in which television images and newspaper front pages overwhelmed us with the macabre discovery of clandestine graves, the product of the ongoing massacres of the «dirty war.»

In Ortega’s story, a dead peasant decides to travel to Lima to ask the president for help in finding the part of his bones that his murderers may have taken to Lima.

The first association I had with this text was with the Incan myth of Incarri, which tells of the dismembered body of the Inca that reassembles itselfs under the earth to be reborn. This character, as a contemporary Incarri, did not wait for his body to be reassemble, but decided to search for his missing bones. But the text, a story written to be read, required a specific treatment to adapt it to the stage. The first step was to review the text and separate what was strictly literatury — describing or referring to what the character was thinking — while privileging the action, the journey, what the character is doing in the present. We also cut out long conversations and parts of the text that might distract the audience in the theater. This treatment of the text was conceived with a solo performance in mind, which also influenced its treatment.

Once the part of the text we were going to work with was defined, Augusto received his first instruction: to learn the lines without interpretation. During the many readings and re-readings, line-throughs, and recognitions of the text, we had a strange, new feeling; no previous process in the group — as far as I can remember — had involved learning the lines, especially for a solo actor in such a long play, without knowing yet how the production would unfold.

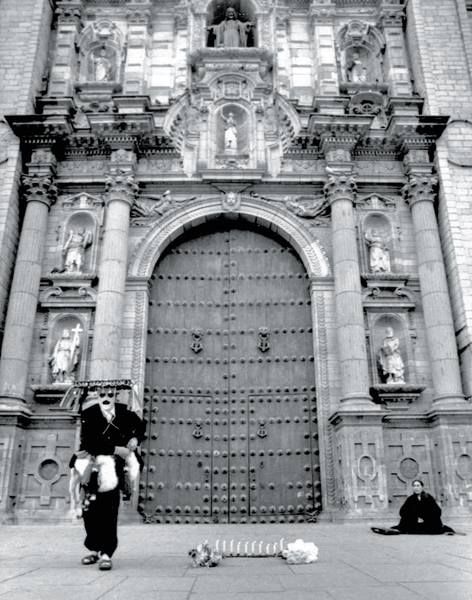

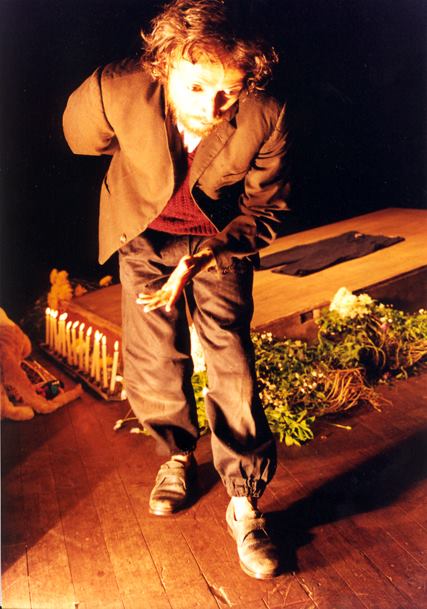

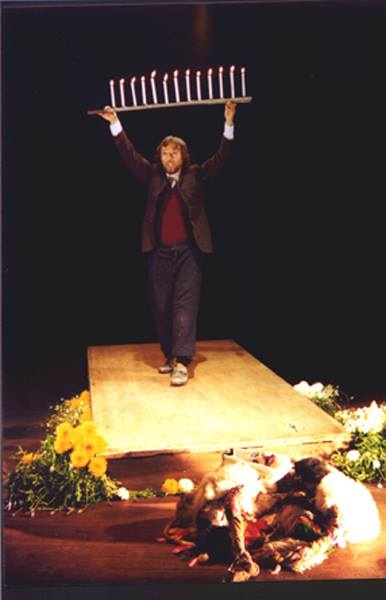

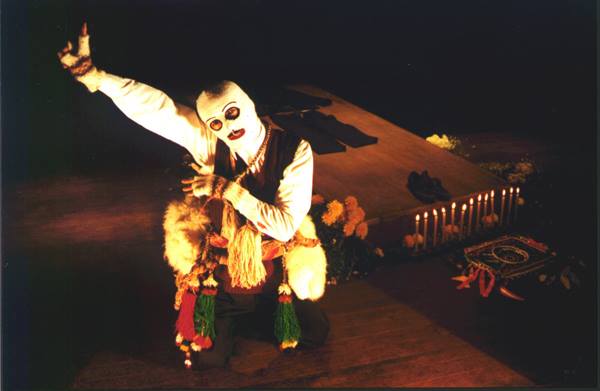

The second moment came when we defined the performance space and theatrical treatment: a funeral ritual in whch the clothes of a disappeared person was laid out in the Andean style. The text was to be spoken in this context and space. A problem to be solved was the treatment of the character: a dead person telling his story, who from the first line declares who he is and what his intentions are — “to go to Lima to recover his…”. How do you embody a character who has no body? Another problem was the strong dramatic tone that the narrative imposes, although there are many moments of humor that we found difficult to accept. Our reading privileged the tragic accent of the text. I must acknowledge the help I received from telling the project to Oswaldo Dragún, who told me: “How terrible, there can be nothing worse. I suppose you’ll do it with a lot of humor, otherwise, what will it be like, right?” This encouraged us to work with Augusto on the Andean comedy that is present in many dances, such as the «chuto» that accompanies the comparsas of Chonguinada in the Mantaro Valley; the «llamichu» of the Fiesta del Agua in Puquio, the Cusco «Majta» or «Pablucha,» that climbs to Coyllurity, among many others. What would happen if one of them told the story? With this question, we went off on a short work trip.

When I returned, Augusto invited me to the theater, and a «Qolla» from Paucartambo (Cusco) told me the story. This was the beginning of the proposal, that later became the relationship between the Qolla and Cánepa — the pact that the Qolla makes with the spirit of the late Alfonso Cánepa to find out what happened to him through the Qolla.

This relationship faced the problem of the body of the absent character and the body of the visible character. Ana helped me with the physical work, suggesting sequences of actions with objects for Augusto, not knowing where they would fit in the narrative these would fit, which I would later rework in relation to the character and specific situations.

The body work was done separately from the text work; the integration of the two came later. From my point of view, it is still possible to influence this body-text dialectic, following the idea that the body comments, anticipates, emphasizes, etc.; nevertheless, the verbal image was so strong that the physical image had to be precise and suggestive.

(Miguel Rubio Zapata, 1990, excerpt)